Altair, Alpha Aquilae (α Aql), is a white main sequence star located at a distance of 16.73 light years from Earth in the constellation Aquila, the Eagle. With an apparent magnitude of 0.76, it is the brightest star in Aquila and the 12th brightest star in the sky.

Altair is one of the nearest stars to Earth visible to the unaided eye. It forms the Summer Triangle asterism with the bright Vega and Deneb, the luminaries of the constellations Lyra and Cygnus. The star pattern dominates the evening sky during the northern hemisphere summer.

Star type

Altair has the stellar classification A7 V, indicating a white star that is still fusing hydrogen into helium in its core. Once thought to be more than 1 billion years old, the star is now believed to be much younger, with an estimated age of around 100 million years.

Altair has 1.86 times the Sun’s mass and an estimated radius of 1.57 – 2.01 solar radii. The star has an equatorial bulge; its radius at the equator is larger than its radius at the poles. With a surface temperature of 6,860 K – 8,621 K, Altair is 10.6 times more luminous than the Sun.

Altair (Alpha Aquilae), image: Wikisky

Altair is a very fast spinner. With a rotational velocity of about 242 km/s, it is the fastest rotating star within 10 parsecs of the Sun. It spins at about 60.5% of its estimated breakup speed (400 km/s). The star has a rotation period of only 7.7 hours. In comparison, the Sun’s rotation period is a little more than 25 days.

Observations with the Palomar Testbed Interferometer (PTI) in 1999 and 2000 revealed that the star had an oblate photosphere as a result of its high rotation rate. Altair’s equatorial diameter is more than 20 percent greater than its polar diameter. The Palomar Testbed Interferometer was a near-infrared long-baseline stellar interferometer that combined the light of three 20-inch telescopes to provide sharpness and allow for high-precision astrometry. It operated from 1995 to 2008.

The groundbreaking study was led by Gerald T. van Belle of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, and David R. Ciardi of the University of Florida. The team measured the star’s radius at different angles on the sky and found that it varied depending on the angle. This indicated that Altair was not perfectly spherical and was the first time that its shape was measured directly. The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal, Volume 559, in 2001.

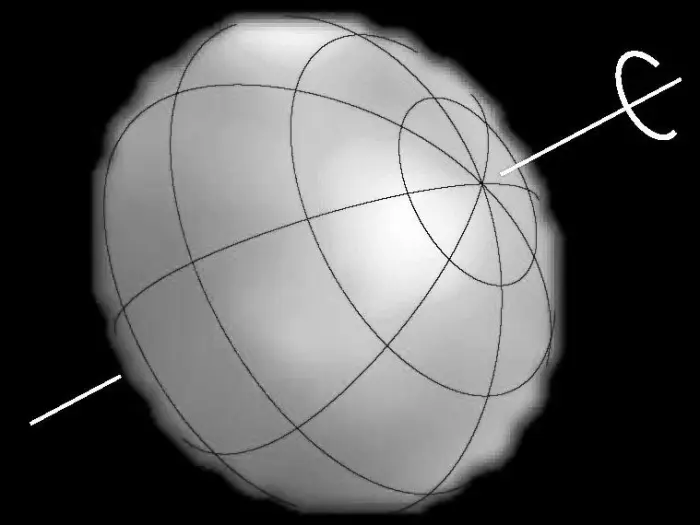

Altair, image: NASA/JPL/Caltech/Steve Golden

Altair was the first main sequence star for which rotational velocity was established from observations of the geometry of its photosphere. The 2001 study gave an estimated rotational velocity (v sin i) of 210 ± 13 km s-1. Other observations in the infrared have confirmed Altair’s flattened shape.

Gravity darkening was confirmed for Altair in 2001 after measurements with the Navy Prototype Optical Interferometer. Gravity darkening is a phenomenon that occurs in rapidly rotating stars whose shape is oblate due to their high rotation rate. Because the surface is closer to the centre of mass at the poles, the star’s surface gravity and temperature are higher at the poles than at the equator. As a result, the poles are more luminous than the equator. Vega in Lyra and Achernar in the Eridanus constellation are two other well-known examples of this.

In 1999, measurements with the Wide Field Infrared Explorer (WIRE) satellite revealed very slight fluctuations in Altair’s brightness, measured in thousandths of magnitude. In 2005, the star was classified as a Delta Scuti variable, a star that shows changes in luminosity as a result of both radial and non-radial pulsations of its surface.

Delta Scuti variables follow the period-luminosity relation in certain passbands – their luminosity is linked to the pulsations – and are used as standard candles to measure distances to star clusters and nearby galaxies. Bright stars in this class include Denebola and Zosma in the constellation Leo, Seginus in Boötes, Caph in Cassiopeia, Tureis in Puppis, and the prototype Delta Scuti in Scutum. Polaris Australis, the South Star, in the constellation Octans also belongs to this group.

A study published in 2021 confirmed the Delta Scuti nature of Altair using the photometric data obtained with the Microvariability and Oscillations of STars (MOST) satellite. Based on the data, a team led by Cécile Le Dizès at Université de Toulouse in France confirmed Delta Scuti-type oscillations in the light curves of Altair and found modal oscillations with amplitude variations with a period of 10 to 15 days.

A study published in 2022 proposed that Altair is the brightest hybrid oscillating star with excited gravito-inertial waves and acoustic waves. A team of scientists led by Michel Rieutord of Université de Toulouse observed the star with the high-resolution spectropolarimeter Neo-Narval at the Pic-du-Midi in the French Pyrenees in September 2020. The astronomers reported the first detection by spectroscopy of waves at the star’s surface, identified as inertial or gravito-inertial waves. This shows that the oscillation spectrum of Altair includes both acoustic modes and gravito-intertial waves.

Facts

Altair is one of the vertices of the Summer Triangle, a prominent asterism also formed by the bright stars Vega in the constellation Lyra and Deneb in Cygnus. Altair is the nearest of the three stars. It is also the coolest and least luminous. It appears brighter than Deneb, but not quite as bright as Vega.

Like Vega, Altair appears bright because it lies in the solar neighbourhood. Deneb, however, shines at first magnitude from a distance of 2,615 light-years. The supergiant has an intrinsic luminosity 196,000 times that of the Sun and is by far the most luminous first-magnitude star, as well as the most distant.

The Summer Triangle, the Northern Cross, and the Shaft of Aquila, image: Wikisky

Altair is also part of the Shaft of Aquila, a line of stars that makes it easy to identify Aquila’s luminary in the night sky in good conditions. Also known as the Family of Aquila, the asterism consists of Altair, the orange bright giant Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae) and the triple star Alshain (Beta Aquilae). With apparent magnitudes of 3.87 and 2.7, Alshain and Tarazed are easily visible next to Altair on a clear night. Tarazed is the second brightest star in Aquila and Alshain the seventh.

The Shaft of Aquila: Altair, Tarazed and Alshain, image credit: Wikimedia Commons/J. Aleu (PD)

Altair is one of the 58 stars selected for use in navigation. Navigational stars are some of the brightest and most identifiable stars in the sky. They have a special status in the field of celestial navigation because they are easy to recognize. They are either exceptionally bright or form distinctive asterisms in the sky. Vega and Deneb are also part of this group.

Altair is on average the 12th brightest star in the sky. It is about as bright as Acrux in the constellation Crux. The two stars are slightly fainter than Betelgeuse in Orion and Hadar in Centaurus, but they (usually) outshine the variable Aldebaran in Taurus, Antares in Scorpius and Spica in Virgo.

Altair is currently located in the G-Cloud complex, an interstellar cloud that also contains Alpha Centauri. The G-Cloud is located next to the Local Interstellar Cloud (the Local Fluff), through which our solar system is currently moving. The Sun is believed to be either embedded in the LIC or in the area which is interacting with the G-Cloud, and it is moving in the direction of the G-Cloud.

In 2006 and 2007, a direct image of Altair was obtained from infrared observations with the Michigan Infrared Combiner (MIRC) on the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) array interferometer on Mount Wilson in California.

An international team led by University of Michigan assistant professor of astronomy John Monnier and graduate student Ming Zhao used optical interferometry and four telescopes separated by almost 300 yards to obtain an image that revealed details of the star’s surface. This made Altair the first main sequence star other than the Sun to have its surface imaged. Altair’s equatorial radius was calculated to be about 2.03 solar radii and its polar radius 1.63 times solar, 25 percent smaller than the radius at the equator. The star’s polar axis is inclined by about 60 degrees to our line of sight.

Image of the rapidly rotating star Altair, made with the MIRC imager on the CHARA Array on Mt. Wilson, credit: Ming Zhao, John Monnier

The CHARA image was the first ever image of a star that provided visual confirmation of gravity darkening. The image showed even more darkening at the equator than scientists had predicted using standard models, highlighting potential flaws in those models.

The mass of 1.86 solar masses was derived in a 2020 study led by astrophysicist Kévin Bouchaud of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur. The team of astronomers used optical long baseline interferometry to study the effects of fast rotation on the stellar surface of Altair and to determine the star’s evolutionary stage and other parameters. They were able to match the spectroscopic, interferometric and asteroseismic data with a single 2D model.

Using ESTER two-dimensional stellar models, the astronomers determined the star’s equatorial radius to be 2.008 ± 0.006 solar radii, its true equatorial velocity, 314 km/s and the rotation period, 7h 46m, or three cycles per day. The team found a mass of 1.86 ± 0.03 solar masses and derived a metallicity of Z = 0.019, indicating that Altair is about 100 million years old. The star was previously believed to be approximately 1.2 billion years old.

The team also found that the star’s core rotates about 50% faster than the envelope and that the surface differential rotation does not exceed 6 percent.

Altair has several fainter visual companions and is listed in the Catalog of Components of Double and Multiple Stars (CCDM), the Aitken Double Star Catalogue (ADS), the Index Catalogue of Visual Double Stars (IDS), and the Washington Double Star Catalog (WDS). However, these stars merely appear in the same line of sight as Altair and are not physically related. They lie at much greater distances from the Sun.

Altair is listed as WDS 19508+0852A in the Washington Double Star Catalog (WDS). Its three dim visual companions are listed as WDS 19508+0852B, C and D. WDS 19508+0852B (mag. 9.82) lies at a separation of 192.1″, WDS 19508+0852C is (mag. 10.3) at a separation of 189.6″, and WDS 19508+0852D (mag. 11.9) at 31.7″ from Altair.

Altair is moving relatively fast against the background of distant stars and will move by as much as a full degree within the next 5,000 years.

Like other bright stars, Altair has been used and mentioned in countless works of fiction. Some of the best-known ones include Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1978), Stephen King’s The Tommyknockers (1987), Anne McCaffrey’s The Rowan (1990), and Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter’s Sunstorm (2005).

Name

The name Altair comes from the Arabic phrase an-nasr aṭ-ṭāʼir, which means “the flying eagle.” The name was officially approved by the International Astronomical Union’s (IAU) Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) on June 30, 2016.

The star’s Arabic name appeared in Egyptian astronomer Al Achsasi al Mouakket’s star catalogue, written in 1650, and was translated into Latin as Vultur Volans. The Arabic name was also used for the asterism Altair forms with Alshain (Beta Aquilae) and Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae).

In India, Altair, Tarazed and Alshain were known as the footprints of Vishnu.

Altair’s Chinese name is 河鼓二 (Hé Gǔ èr), meaning “the second star of the drum at the river” or “river drum two.” The name refers to the Chinese asterism known as “the river drum” (河鼓). The asterism consists of Altair, Tarazed and Alshain.

In Chinese culture, Altair is well-known for its association with the myth of the cowherd and the weaver girl, in which Niulang, the cowherd (represented by Altair), and his two children (represented by Tarazed and Alshain) are separated by a large river (the Milky Way) from Zhinu, the weaver girl (represented by Vega), Niulang’s wife. They can only meet once a year when magpies create a bridge to allow them to cross the celestial river. In Chinese lore, Altair is known as “the cowherd star” (Niú Láng Xīng, 牛郎星).

The meeting of the star-crossed lovers is celebrated during the annual Qixi Festival, held on the seventh day of the seventh month on the Chinese lunar calendar. The tale also inspired the Tanabata festival in Japan, which celebrates the meeting of Orihime (Vega) and Hikoboshi (Altair), and the Chilseok festival in Korea, associated with the legend of Jiknyeo (the weaver girl) and Gyeonwu (the cowherd).

The Summer Triangle with Vega (top left), Altair (lower middle) and Deneb (far left), image: NASA, ESA. Credit: A. Fujii

In Micronesia, Altair is known as Mai-lapa, or “big/old breadfruit.” The Māori people of New Zealand knew the star as Poutu-te-rangi, or “the pillar of heaven.” The Koori people in Victoria in Australia called it Bunjil, the wedge-tailed eagle (Australia’s largest predatory bird), and Tarazed and Alshain were known as black swans, his two wives.

The people of the Murray River in Australia associated the star with the story of the river’s formation and called it Totyerguil, after a mythical hunter who speared a giant cod. In local lore, the wounded cod created a channel across southern Australia and moved to the sky as the constellation Delphinus.

Location

Altair is easy to identify because it is part of the Summer Triangle and has two relatively bright stars – Alshain and Tarazed – on either side. The three stars in Aquila are part of the larger eagle-shaped asterism that flies across the sky opposite Cygnus, the Swan. Altair marks the Eagle‘s head or neck and it is facing the small but distinctive constellation Delphinus.

The Summer Triangle is a large and prominent asterism visible high overhead during the northern hemisphere summer. It is formed by Altair with the bright stars Vega in the Lyra constellation and Deneb in Cygnus.

The location of Altair (α Aquilae), image: Stellarium

Constellation

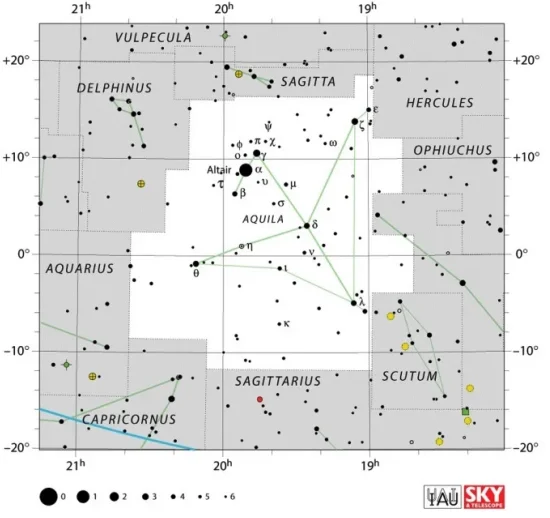

Altair is the luminary of the constellation Aquila, the Eagle. Aquila is one of the Greek constellations, first listed by the Greco-Roman astronomer Ptolemy of Alexandria in his Almagest in the 2nd century CE. Occupying an area of 652 square degrees, it is the 22nd constellation in size.

Aquila constellation map by IAU and Sky&Telescope magazine

Aquila hosts many notable stars. Other than Altair, these include the orange bright giant Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae), the orange giant Epsilon Aquilae, the variable yellow-white supergiant Eta Aquilae, the triple star system Alshain (Beta Aquilae), the binary star Okab (Zeta Aquilae), and the semiregular variable carbon star V Aquilae.

Aquila contains several notable deep sky objects. These include the planetary nebulae NGC 6781, NGC 6778, NGC 6751, also known as the Glowing Eye Nebula, and NGC 6741, nicknamed the Phantom Streak Nebula, the open clusters NGC 6709 and NGC 6755, and the globular cluster NGC 6760.

The best time of the year to observe the stars and deep sky objects of Aquila is during the month of August, when the Eagle flies high overhead in the evening for northern observers. The entire constellation is visible from locations north of the latitude 75° S.

The 10 brightest stars in Aquila are Altair (Alpha Aql, mag. 0.76), Tarazed (Gamma Aql, mag. 2.712), Okab (Zeta Aql, mag. 2.983), Theta Aquilae (mag. 3.26), Delta Aquilae (mag. 3.365), Lambda Aquilae (mag. 3.43), Alshain (Beta Aql, mag. 3.87), Eta Aquilae (mag. 3.87), Epsilon Aquilae (mag. 4.02), and 12 Aquilae (mag. 4.02).

Altair – Alpha Aquilae

| Spectral class | A7V |

| Variable type | Delta Scuti |

| U-B colour index | +0.09 |

| B-V colour index | +0.22 |

| V-R colour index | +0.14 |

| R-I colour index | +0.13 |

| Apparent magnitude | 0.76 |

| Absolute magnitude | 2.22 |

| Distance | 16.73 ± 0.05 light-years (5.13 ± 0.01 parsecs) |

| Parallax | 194.95 ± 0.57 mas |

| Radial velocity | −26.1 ± 0.9 km/s |

| Proper motion | RA: +536.23 ± 0.51 mas/yr |

| Dec.: +385.29 ± 0.47 mas/yr | |

| Mass | 1.86 ± 0.03 M☉ |

| Luminosity | 10.6 L☉ |

| Radius | 1.57 – 2.01 R☉ |

| Temperature | 6,860 – 8,621 K |

| Metallicity | -0.2 dex |

| Age | 100 million years |

| Rotational velocity | 242 km/s |

| Rotation | 7.77 hours |

| Surface gravity | 4.29 cgs |

| Constellation | Aquila |

| Right ascension | 19h 50m 46.99855s |

| Declination | +08° 52′ 05.9563″ |

| Names and designations | Altair, Alpha Aquilae, α Aql, 53 Aquilae, HD 187642, HR 7557, HIP 97649, SAO 125122, LTT 15795, LHS 3490, BD+08°4236, GCTP 4665.00, WDS 19508+0852A, GJ 768, FK5 745, AG+08 2636, LFT 1499, NLTT 48314, TYC 1058-3399-1, JP11 3142, PPM 168779, 2MASS J19504698+0852060, GC 27470, GCRV 12193, UBV 16885, IRAS 19483+0844, ADS 13009 A, IDS 19459+0836 A, CCDM J19508+0852A, WDS 19508+0852A |